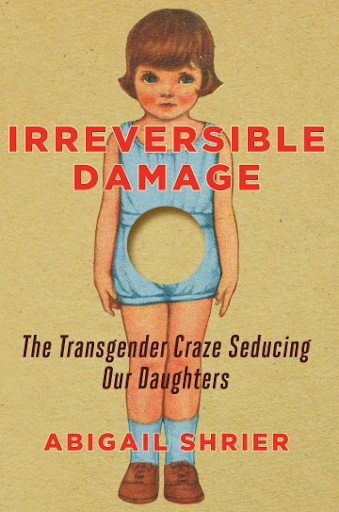

Grey Weinstein (he/they/xe) I would be far from the first person to point out that the fight for abortion access and the fight for gender affirming healthcare are intrinsically linked. Just as restrictions on abortion threaten pregnant people’s right to choose whether they want to be pregnant (and to assume all of the financial and physical risk that pregnancy entails), so too do restrictions on medical transition threaten trans people’ right to choose what we do with our bodies. Thus at their core, both issues are a struggle for bodily autonomy and agency over personal medical decisions. Restrictions on both abortion access and gender affirming care also both operate to target marginalized groups, furthering systemic oppression – trans people certainly are an oppressed class, as are women and others who can get pregnant. (As an aside, it is important to recognize that trans men and nonbinary people can and do need abortions, and even more important to elevate the unique needs of pregnant transmasculine folks for whom reproductive healthcare comes with a host of additional challenges. At the same time, it is also necessary to acknowledge that abortion bans are a tool of institutionalized misogyny which seek to deny (cis) women, among others, agency over their bodies.) As statewide legislative attacks on gender affirming care providers ramp up alongside abortion restrictions, it is clear that conditions are dire for many who seek these types of medical care. Anti-abortion and anti-trans health efforts share similar rhetoric. As part of the project of fear-mongering over the “irreversible” nature of HRT and gender affirming surgeries, transphobic healthcare providers use the same playbook as anti-choice “crisis pregnancy centers.” Both insist on “100 percent certainty” from patients and weaponize the possibility of regret in order to deter patients from seeking care, undermining individual autonomy and decision making. Furthermore, transphobic medical rhetoric contains much hand-wringing about the potential “infertility” of trans patients as a result of gender affirming care. (While taking hormones, either feminizing or masculinizing, does not make one infertile, gender affirming surgeries like hysterectomies or orchiectomies do.) This sentiment echoes the anti-choice framework which positions those who can get pregnant as mere potential incubators for future babies, rather than individuals in our own right with worth outside of our reproductive capabilities. Just take a look at the cover of Abigail Shrier’s transphobic screed, “Irreversible Damage,” which features the image of a white little girl with an enormous hole in her abdomen. The (racialized) implications of this imagery – that the so-called “transgender craze seducing our daughters” threatens the reproductive capacity of young women – is anything but feminist, positioning transmasculine people as nothing more than potential future birthgivers. (It also invokes a certain victimization of white femininity which equates whiteness to purity and innocence. Shrier seems to implicitly suggest that the loss of white reproductive capacity poses a threat to the future of the race in a manner akin to replacement theory.)  The cover of "Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters" features a little girl with a gaping hole in her stomach, symbolizing the loss of her uterus. This image sums up Shrier's view of transgender men and transmasculine people: as deluded and helpless girls whose defining feature is our ability to get pregnant. From this shared conservative ideology, anti-abortion and anti-trans actors have built their nation-wide assault on bodily autonomy using the same strategies. State-level legislation targeting healthcare providers has started at a level that, while still disastrous, is relatively small. For instance, several states are moving to ban gender affirming care only for minors, while others are banning abortion but only at six weeks. These (still very harmful) laws will inevitably ramp up towards their end goal of total healthcare bans. Indeed, this acceleration is already underway, as 12 states are currently enforcing near-total abortion bans and several more have proposed restrictions on medical transition for adults. And the outcome of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization not only overturns Roe v. Wade but also sets the stage for the reversal of the right to privacy. This can only spell bad news for trans healthcare and LGBTQ+ rights as a whole. But if the threats to our futures are intertwined, then surely our liberation is also connected. As anti-choice activists and transphobes draw from the same playbook, now is a good time to remind ourselves that pro-choice activists and trans liberationists likewise have always used similar organizing strategies, and will continue to do so in the future. And of course, pro-choice and pro-trans actors don’t belong to two discrete groups; rather, the same individuals and organizations which fight for the safety and dignity of abortion patients often do the same for trans people. Indeed, many people fall into the category of both “people seeking abortions” and “people seeking gender affirming care.” Even in instances in which these two groups don’t overlap, solidarity between the reproductive justice movement and the trans liberation movement is one of our greatest strengths. To be frank, writing this article is something of a therapeutic exercise for myself. It is an effort to find hope, not because I feel hopeful (I most certainly do not), but rather because hope is a political necessity. As the news grows more and more worrisome for trans people and those who can get pregnant, I know I’m not the only one fighting off despair and apathy in order to find the motivation to organize for our rights. What keeps me from complete surrender is the work that my community members are putting in to protect the most vulnerable as things continue to get worse. With that in mind, below I outline three strategies that activists have employed or are currently employing to expand access to abortion and gender affirming healthcare: sanctuary state laws, mutual aid, and extralegal surgery providers. It is my hope that these examples will energize others to, if not join the fight, at least maintain some optimism.

In the context of abortion, sanctuary states have made efforts not only to fund abortion itself but also to cover costs associated with the procedure for out-of-state patients such as lodging and transportation. New York led this movement by setting aside $35 million to cover the cost of abortions, with much of this money going directly to abortion clinics. Similarly, in 2022 Oregon’s state legislature passed legislation establishing the Reproductive Health Equity Fund, which allocated $15 million towards the reproductive justice nonprofit Seeding Justice. Organizers on the ground will be able to use these funds to cover the cost of transportation or housing for people seeking abortions in Oregon, including those who have traveled to Oregon from out of state. Other states have followed suit; to name just a few, in 2022 the city of Chicago alone approved a $500,000 fund to cover similar abortion-related costs, while California pledged $20 million towards logistical costs including transportation and childcare. Sanctuary states for abortion have also sought to expand access to abortion by increasing the number of doctors allowed to perform abortions. For example, a bill that went into effect in California at the start of 2023 allows nurse practitioners and certified nurse-midwives, both of which are trained healthcare professionals, to provide abortion without doctor supervision. Policies like this increase access to safe and legal abortion by freeing up more reproductive health experts and thus decreasing wait times. Other potential solutions to questions of access include training more doctors to prescribe abortion pills. Sanctuary states can also take some measures to prevent out-of-state abortion seekers from being prosecuted by the states in which they reside. For instance, Connecticut has passed legislation to protect the privacy of out-of-state patients’ medical records, and tweaked their extradition laws to prevent individuals from being criminally charged by their home states. California passed a similar law in 2022 pertaining to trans healthcare. Senate Bill 107 prevents the prosecution or extradition of healthcare providers who offer gender affirming care. Like the Connecticut law protecting the confidentiality of abortion seekers, this legislation also seals the medical information of trans patients. California’s Medicaid program also covers a variety of types of gender affirming healthcare. Additionally, California law forbids health insurance companies from discriminating on the basis of gender identity, which prevents private insurance from refusing to cover trans related care. In short, sanctuary state laws can offer desperately-needed medical care to both trans patients and patients seeking abortions, as well as protecting them from persecution by majority-Republican states. As more and more trans people flee conservative states, and abortion bans continue to be passed through state legislatures, these policies can create a safe haven for many. Of course, one must keep in mind that the most marginalized members of both communities often don’t have access to the resources to cross state lines; more often than not, those who can afford to pack up and move in pursuit of an abortion or a trans-friendly state have access to wealth that many others lack. This is not to say that fleeing one’s state to access needed healthcare is a privilege. Rather, it is a reminder that while sanctuary states are a triumph for the pro-choice and pro-trans cause, they are not sufficient. In my personal opinion, no solution which leaves intact the systems of power which actively oppress trans people and pregnant people is enough, which is why no strategy which works within the guidelines of the state will ever lead to liberation. At the same time, such legal strategies can work towards harm reduction in a political moment where we must use all of the tools at our disposal. It remains to be seen whether other states will follow California in becoming trans sanctuary states, as they have in the case of abortion. Regardless, we must continue to fight for reproductive justice and trans liberation in every state, especially the conservative ones where vulnerable groups risk being left behind. 2. Mutual Aid Where the state fails to provide for the needs of marginalized populations, community members can step in to fill the gaps through mutual aid. Simply put, mutual aid is when individuals come together to meet one another’s needs, without the participation of the government or the nonprofit industrial complex. Mutual aid is much-lauded by scholars for its revolutionary potential – when community members get together to provide for one another, they can help each other understand how the state’s failure to meet their needs is indicative of wider systemic problems, and can build collective power to oppose capitalist and racist institutions. In the context of abortion and trans healthcare, there is a long history of communities using mutual aid to widen access to care. Mutual aid has long been used to help people access abortion. During the period in which abortion was legal, this might include community members pitching in monetarily to help one another afford safe and legal abortions, driving pregnant people to abortion clinics, or offering them temporary housing or childcare when seeking an abortion. Post-abortion care, especially in the case of surgical abortions, is another resource that individuals could exchange through mutual aid networks. The provision of these basic needs is likewise often facilitated through mutual aid within transgender communities. One could turn to historical examples like STAR House, the shelter for trans youth and sex workers run by Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in the 1970s, as exemplifying the solidarity and community-led direct action that are key aspects of mutual aid. Even in modern everyday life, most trans people are likely familiar with the ways in which mutual aid appears in our communities – the exchange of money, food, gender affirming items like binders or makeup, clothing, post-surgical care, etc that trans people give one another to keep ourselves alive. Today, both abortion seekers and trans people might use the internet to crowdfund for their medical needs, relying on community members to chip in so they can access these treatments. Those seeking access to abortion or gender affirming care share another powerful mutual aid tool: the exchange of medical resources and information. In the pre-Roe era, the spread of information about chemically induced abortions was crucial to empowering many pregnant people who sought care. Similarly, in the early days of hormone replacement therapy, many trans people helped one another acquire black market HRT. Mutual aid efforts to directly connect people with the medical resources they need to survive and thrive, both for pregnant people and trans people, evidently share some key characteristics. Both see radical potential in empowering people to exercise agency over their own medical decisions and thus their own bodies. Both understand the criminalization of healthcare as a (misogynistic, transphobic) effort to deprive individuals of bodily autonomy, and reject the legitimacy of such immoral laws. Above all, both directly challenge state repression by building collective power parallel to and outside of the state; both pregnant people and trans people rely on their communities to keep them safe and cared for. Whether it is community based funds for abortion costs or the illicit exchange of abortion pills, crowdfunding for gender affirming surgery or the sharing of HRT, mutual aid continues to have a central role in both the struggle for abortion and for trans liberation. 3. Extralegal Surgery Providers This last strategy utilized by both reproductive justice activists and trans activists is most certainly a form of mutual aid itself, but I’ve decided to dedicate a separate section to it because it is so markedly different from the other manifestations of mutual aid which I have discussed so far. When lifesaving healthcare is criminalized, there will always be some individuals who are willing to provide that care regardless of what the law says. That is certainly the case when it comes to black market HRT providers or abortion pill providers, whether it is motivated by a courageous dedication to bodily autonomy or from a desire to charge money to a vulnerable group with few alternatives. A riskier but just as necessary form of this type of mutual aid is those who provide surgery even after it has been banned. In the case of abortion access, the Jane Collective is the most wide-scale example of community organizing to provide (criminalized) surgical abortion to those who needed it. From 1969 to 1973 when Roe v. Wade legalized abortion, the Jane Collective connected pregnant people in Chicago to abortion providers. Many of the Collective’s members were doctors who were willing to commit to their values regardless of legality, while others were reproductive justice activists or midwives. Still others were self-taught to perform abortions safely without doctor supervision. The story of the Jane Collective’s work was part of Eilís Ní Fhlannagáin’s inspiration when she started conducting gender affirming surgeries out of a barn in Washington. Trans women seeking gender affirming surgery faced barriers to access due to the high cost of the procedure, scarcity of doctors willing to work with trans patients, and gatekeeping medical policies designed to turn away as many trans patients as possible. Ní Fhlannagáin and one of her friends, a doctor who is now an abortion provider and chose to remain anonymous, offered orchiectomies to trans women at a low cost. Although the barn-turned-clinic was certainly not a state sanctioned operation, it was technically not illegal; the friend who performed the surgery was in medical residency, and Ní Fhlannagáin herself went through medical privacy law training. They made so little money that they did not even need a business license. Both Ní Fhlannagáin’s orchiectomy clinic and the Jane Collective thus represent a commitment to providing healthcare to the most marginalized community members, regardless of what the law has to say. While I certainly wouldn’t recommend getting bottom surgery in a barn as a first resort, however technically legal it might be, Ní Fhlannagáin’s story remains an incredible example of how healthcare providers and activists can live their values through the provision of stigmatized or difficult to access care. Ní Fhlannagáin herself stated that “abortion issues and trans healthcare issues, they're the exact same fight,” in a 2022 interview with “The Independent.” Her work, and the work of the Jane Collective, have helped an untold number of people access healthcare when they needed it most. As activists on the ground continue to organize in support of abortion and trans healthcare access, it remains to be seen what creative and life saving solutions our communities might soon generate. Regardless, it is clear that we are building on a rich history of community care, collective action, and resistance to state oppression. Are you feeling hopeful? I’ll be honest, I’m not optimistic. But I do have faith in my community members who I see every day advocating for our right to exist. At the very least, we won’t go down without a fight.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search by typing & pressing enter