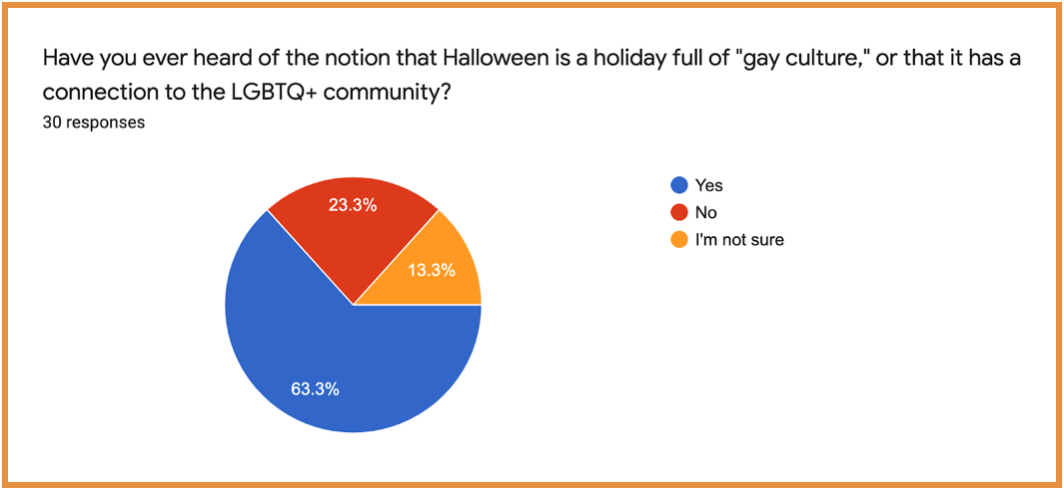

Atticus Spicer (they/he)The history of Halloween winds as much as the long, twisted, tree-shrouded road leading to a haunted house. Simultaneously a pagan-based holiday, highly profitable affair, celebration teeming with religious iconography, and extravagant camp-infused party, Halloween holds unique meanings for different groups.  With this year’s Halloween likely taking a nontraditional, socially distant route, it’s time to take a look at the holiday’s unconventional history - and it’s surprising connection to the queer community. Illustration by Atticus Spicer. With this year’s Halloween likely taking a nontraditional, socially distant route, it’s time to take a look at the holiday’s unconventional history - and it’s surprising connection to the queer community. Illustration by Atticus Spicer. As such, Halloween's origins also face contestation, but the most agreed upon part of the holiday’s roots is that they are grounded in Samhain, a Celtic marker for the end of summer and the beginning of the new year. Historically, Samhain functioned mostly as a festival preparing for the coming winter, involving taking stock of one’s inventory and finalizing the harvest. It also coincided with a period of supernaturally charged energy, in which dark forces had to be warded off with various rituals and occasional sacrifices. According to historian Nicholas Rogers in his book “Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night,” “Many stress [Samhain’s] elemental primitivism and its enduring legacy to the character of Halloween, particularly in terms of its omens, propitiations, and links to the otherworld.” Since then, even the legacy of these “omens, propitiations, and links to the otherworld” have undergone drastic changes, creating a Halloween fitting for the standards of modernity (i.e. less sacrifices, more camp and capitalism). Somewhere along the line, Halloween obtained a special place within the gay culture developing in the United States and other Western countries, eventually resulting in what some call “the gay Christmas.” Although plenty within the LGBTQ+ community do not celebrate Halloween and there isn’t a collective agreement about which component draws in queer individuals, several thought-provoking connections still exist. Of all of Halloween’s allure, the propensity for camp, the oxymoronic embrace of nonconformity, and the capacity for rebellion all contribute to a holiday that, year after year, manages to draw in scores of delighted LGBTQ+ revelers. But where did these trends begin and how did the queer community influence the holiday’s development? Unsurprisingly, the history of Halloween’s connection to the gay community and camp - the exaggerated, deliberately flamboyant aesthetic common within gay culture - arguably starts in Greenwich Village in New York City. The largest Halloween parade in the world, the Village Halloween Parade, began in 1974 with artist and puppeteer Ralph Lee seeking a community-based Halloween celebration where participants could indulge with extravagant costumes and an art-friendly environment. The event quickly grew - to over two thousand by the second year and a quarter million by the fifth. Aided by the community’s artistic and welcoming character, the parade attracted participants interested in drag, sexual expression, social commentary, and overall glamorous ensembles. One attendee from the first year, Jill Lynne, remembers, “A sense of creative freedom prevailed, and an unexpected enormous turnout from the community and their friends arrived. There were artists, families, drag queens, and proud members of the LGBT community… The night felt episodic, and it was exhilarating.” While this event wouldn’t remain predominantly queer, the impact of the drag shows and general LGBTQ-influenced portions of the parade endure in today’s holiday traditions. As Rogers describes the body politics and camp of Halloween, “At its best, Halloween functions as a transient form of social commentary...Here the public liminality of the night, the holiday’s capacity to transcend everyday social constraints…intersects with the artistic avantgarde.” Such characterization of Halloween continues, with modern parades and parties growing saturated with excess. The more outrageous the party, the better, a trait undoubtedly inspired by the initial gay celebrations of the 70s and 80s. As some have noted, the tendency of the gay community to celebrate Halloween in such a grandiose manner might have roots in the fact that Pride during the time served almost exclusively as political demonstration. In that context, Halloween became the de facto celebration of one’s sexuality, akin to the actual Pride parades of today. Halloween, as a holiday associated with countercultural ideas rather than pure protest, offered a space for not only commemorating one’s identity, but doing so in style. In a similar vein as camp, Halloween has almost always relied upon what Rogers calls “transcending everyday social constraints.” For the queer community, crossdressing or experimenting with one’s gender expression marked such transcendence, a trend that both persists today and links back to some of the oldest Halloween traditions in the United States. One of the earliest recorded instances of crossdressing for one’s Halloween costume comes from an early 20th century Pittsburgh newspaper. The headline of one article from The Pittsburg Press, Halloween night in 1912, read, “HALLOWEEN TO BE MAD FROLIC IN PITTSBURG: Gay Maskers Will Throng Streets and Parties Will Be Held in Many Households in Pittsburg District: POLICE WILL MAINTAIN ORDER IN THE STREETS.” Said article proceeded to describe certain moral codes that needed to be upheld during Halloween festivities, including, “No girls or women are allowed to appear in masculine attire.” When women did appear in such attire, the police held true on their threat to maintain order, arresting several for their costume choices. But the law became so widely disregarded that the same Pittsburgh police force abandoned the cause only two years later, publicly announcing, “Women dressed in male attire will not be molested unless they are disorderly or seen entering saloons.” Such a quick reversal demonstrates how pervasive “crossdressing” proved to be; for transgender, nonbinary, or genderfluid revelers, Halloween served as the one time in which any expression of their identity was allowed. Perhaps an even more blatant indication of the desire to dress differently comes from Charles Frederick White's 1908 poem "Hallowe'en." It reads, “The women dressed in men’s attire; The small girl, too, quenched her desire, To get into her brother’s pants.” Today, dressing in clothing associated with the opposite sex for a Halloween costume doesn’t seem that out of place. But for years, costumes have presented the only opportunity to experiment with one’s gender expression, to manipulate codified clothing for one’s temporary benefit. The freedom to dress according to one’s gender identity all nights of the year, of course, has been hard earned, involving a long and intensive political battle that still continues - and surprisingly, Halloween has helped play into that as well. During the 1970s and 80s, televangelist Jerry Falwell catered to the so-called “Moral Majority,” broadcasting his beliefs directly into the public’s homes in his attempt to enliven a resurging religious right. One of the dominant causes in his crusade involved fighting what he called "a massive homosexual revolution," and in the process of waging this war against “the gays,” Falwell turned to Halloween for help. In creating “Hell Houses,” which are essentially righteous haunted attractions put on by Christian groups, Falwell sought to literally scare participants into avoiding homosexuality. Within these attractions, each room acts as a demonstration of a different sin or social issue, using actors in demonic costumes to warn against falling into Satan’s grasp. One church now offers a purchasable kit for homemade Hell Houses, consisting of scenes about abortion, domestic violence, and drug use. As expected, the LGBTQ+ community has featured prominently as one of the sins people can fall victim to, with a “gay marriage” scene also included in the low price of $299. Whether or not these Hell Houses have been especially effective in persuading participants away from homosexuality can be debated, but they undoubtedly exemplify the ways in which the horror of Halloween can be weaponized against the gay community. Halloween, as an already unconventional holiday, serves as both a haven for queer individuals who have been marginalized by society and as a tool for homophobes to take a moralistic stand. In this, Halloween offers a chance for one side to enforce the status quo and the other to rebel against it. At least in part, this rebellion unquestionably helps maintain Halloween as the, ironically dubbed, “gay Christmas.” To bring this story to a modern and local close, I sought out the perspectives of the LGBTQ+ community here at the University of Michigan, surveying thirty different LGBTQ+ students on what they feel connects the community to Halloween. The results varied greatly, though nearly everyone has at least a history of celebrating Halloween and most felt either positively or indifferent towards the holiday. (Only one person had never celebrated it, and one other felt purely negative about it.) Following that, when asked about whether or not the respondent felt Halloween was connected to their identity, the results leaned surprisingly towards “no.” In fact, 70% felt that Halloween has nothing to do with their identity at all. When asked to elaborate, the majority of respondents who felt there was no connection explained that Halloween is fun regardless of a person’s identity, pointing to traditional, non-queer related aspects of the holiday they enjoy. One respondent wrote, “Halloween has always been fun for me regardless of my identity,” and another similarly explained, “I don't do things on Halloween solely because of my sexual identity.” However, for the people who felt Halloween did relate to their identity, they often described the importance of using costumes as self-expression, echoing the decades-old use of Halloween as a conveyance of gender identity. One respondent who identifies as trans and nonbinary elaborated, “[Halloween] was a chance to be someone or something else... It's difficult not to connect that with my journey of gender identity and self exploration.” Put even more explicitly, another expressed how “[Halloween] gives me a chance to embrace the most extreme and experimental whims of my gender presentation.” In a fun, fascinating turn, when asked if they knew about the concept of Halloween being full of “gay culture,” an affirming majority caught on immediately. One participant confirmed the basis of this article with a hilarious elaboration of, “Yes, it is Christmas for gays.” Another pointed to the community’s love of “camp, glamor, and altered identity,” and yet another noted a potential connection with Halloween’s “association with spooky things and counterculture...as LGBT members are often pushed to the counterculture as well, I can see some sort of connection forming from that.” Many students expressed appreciation for Halloween’s capacity to accept the LGBTQ+ community. Several cited the “sense of safety,” “lack of fear from judgement,” and “open expression” of the holiday as reasons they may feel connected to Halloween through more than just baseline enjoyment. Finally, in perhaps the most encouraging portion of responses, for students who elaborated on why they don’t think Halloween has a connection to the LGBTQ+ community, or why they aren’t entirely sure, the responses were overwhelmingly interested in learning more. One succinct reply encapsulated this stance perfectly, “I have not heard this but I’d love to hear more about it!” It is my only hope that this article has enabled exactly that. We hope you have a happy Halloween.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search by typing & pressing enter